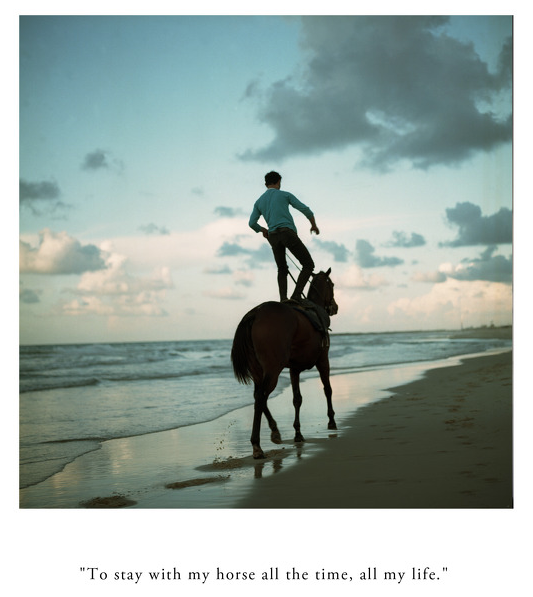

/Shatila, photo © Ivana Perić, MER/

/Shatila, photo © Ivana Perić, MER/

Summer of 1982 was a long time ago, but mention it to anyone living in Lebanon, anyone Palestinian and/or Israeli, they probably remember it very well. That’s what war does, it shapes your memory, distorts it, occupies it. War’s a little ghost that keeps clinging to your chest.

Summer of 1982 was a long time ago, but it’s important to go back in time, to see what happened, to see how it reflects in what we witness today (war is peace?). Following is an excerpt from Noam Chomsky’s book The Fateful Triangle.

✍

On June 6, 1982, a massive Israeli expeditionary force began the long expected invasion, Operation “Peace for Galilee,” a phrase “which sounds as if it comes directly out of the pages of 1984,” as one Israeli commentator wrote:

Only in the language of 1984 is war-peace and warfare-humane. One may mention, of course, that only in the Orwellian language of 1984 can occupation be liberal, and there is indeed a connection between the “liberal occupation” [the Labor Party boast] and a war which equals peace.

Excuses and explanations were discarded almost as quickly as they were produced: the Argov assassination attempt, defense of the border settlements, a 25-mile limit. In fact, the army headed straight for Beirut and the Beirut-Damascus highway, in accordance with plans that had long been prepared and that were known in advance to the Labor opposition. Former chief of military intelligence Aharon Yariv of the Labor Party stated: “I know in fact that going to Beirut was included in the original military plan,” despite the pretense to the contrary, dutifully repeated by the U.S. government, which could hardly have been in much doubt about the facts if U.S. intelligence was not on vacation.

Extermination of the Two-Legged Beasts

The first target was the Palestinian camp of Rashidiyeh south of Tyre, much of which, by the second day of the invasion, “had become a field of rubble.” There was ineffectual resistance, but as an officer of the UN peace-keeping force swept aside in the Israeli invasion later remarked:

“It was like shooting sparrdws with cannon.” The 9000 residents of the camp-which had been regularly bombed and shelled for years from land, sea and air-either fled, or were herded to the beach where they could watch the destruction of much of what remained by the Israeli forces. All teen-age and adult males were blindfolded and bound, and taken to camps, where little has been heard about them since.

This is typical of what happened throughout southern Lebanon. The Palestinian camps were demolished, largely bulldozed to the ground if not destroyed by bombardment; and the population was dispersed or (in the case of the male population) imprisoned. Reporters were generally not allowed in the Palestinian camps, where the destruction was worst, to keep them from witnessing what had happened and was being done. There were occasional reports. David Shipler described how after the camps were captured the army proceeded to destroy what was left. An army officer, “when asked why bulldozers were knocking down houses in which women and children were living,” responded by saying: “they are all terrorists.” His statement accurately summarizes Israel’s strategy and the assumptions that underlie it, over many years.

There was little criticism here of Israel’s destruction of the “nests of terrorists,” or of the wholesale transfer of the male population to prison camps in Lebanon and Israel-or to their treatment, discussed below. Again, one imagines that if such treatment had been meted out to Jews after, say, a Syrian conquest of Northern Israel, the reaction would have been different, and few would have hesitated to recall the Nazi monsters. In fact, we need not merely imagine. When a PLO terrorist group took Israeli teen-age members of a paramilitary (Gadna) group hostage at Ma’alot, that was rightly denounced as a vicious criminal act.

Since then, it has become virtually the symbol of the inhuman barbarism of the “two-legged beasts.” But when Israeli troops cart off the Palestinian male population from 15 to 60 (along with many thousands of Lebanese) to concentration camps, treating them in a manner to which we return, that is ignored, and the few timid queries are almost drowned in the applause-to which we also return-for Israel’s display of humanitarian zeal and moral perfection, while aid is increased in honor of this achievement. It is a scene that should give Americans pause, and lead them to raise some questions about themselves.

Israel’s strategy was to drive the Palestinians to largely-Muslim West Beirut (apart from those who were killed, dispersed or imprisoned), then to besiege the city, cutting off water, food, medical supplies and electricity, and to subject it to increasingly heavy bombardment. Naturally, the native Lebanese population was also severely battered. These measures had little impact on the PLO guerrilla fighters in Beirut, but civilians suffered increasingly brutal punishment. The correct calculation was that by this device, the PLO would be compelled to leave West Beirut to save it from total annihilation.

It was assumed, also correctly, that American intellectuals could be found to carry out the task of showing that this too was a remarkable exercise in humanity and a historically unique display of “purity of arms,” even having the audacity to claim that it was the PLO, not the Israeli attackers, who were “holding the city and its population hostage”-a charge duly intoned by New York Times editors and many others.

/Green Line, Beirut, 1982/

/Green Line, Beirut, 1982/

Dan Connell, a journalist with wartime experience and Lebanon project officer for Oxfam, describes Israel’s strategy as follows:

The Israeli strategy was obvious. They were hitting a broad belt, and they kept moving the belt up toward the populated area and pushing the people in front of it. The Israelis forced an increasing concentration of people into a smaller space, so that the casualties increased geometrically with every single shell or bomb that landed.

The attackers used highly sophisticated U.S. weapons, including “shells and bombs designed to penetrate through the buildings before they explode,” collapsing buildings inwards, and phosphorus bombs to set fires and cause untreatable burns. Hospitals were closed down or destroyed.

Much of the Am el-H ilweh refugee camp near Sidon was “flat as a parking lot” when Connell saw it, though 7-8000 Palestinians had drifted back-mostly women and children, since the men were “either fighting or arrested or dead.” The Israelis bulldozed the mosque at the edge of the camp searching for arms, but “found 90 or 100 bodies under it instead, completely rotted away.” Writing before the Beirut massacres but after the PLO had departed, he notes that “there could be a bloodbath in west Beirut” if no protection is given to the remnants of the population.

The Israeli press also reported the strategy of the invading army. One journalist observing the bombardment of Beirut in the early days describes it as follows:

With deadly accuracy, the big guns laid waste whole rows of houses and apartment blocks believed to be PLO positions. The fields were pitted with craters. . . Israeli strategy at that point was obvious-to clean away a no-man’s land through which Israeli tanks could advance and prevent any PLO breakout.

The military tactics, as widely reported by the Israeli and foreign press, were simple. Since Israel had total command of the air and overwhelming superiority in firepower from land, sea and air, the IDF simply blasted away everything before it, then sent soldiers in to “clean out” what was left. We return to some descriptions of these tactics by Israeli military analysts. The tactics are familiar from Vietnam and other wars where a modern high technology army faces a vastly outmatched enemy. The difference lies in the fact that in other such cases, one rarely hears tales of great heroism and “purity of arms,” though to be accurate, these stories were more prevalent among American “supporters” than Israeli soldiers, many of whom were appalled at what they were ordered to do.

Economist Middle East correspondent G. H. Jansen describes Israel’s tactics in the first days of the war as follows: to surround cities and towns “so swiftly that civilian inhabitants were trapped inside, and then to pound them from land, sea and air. After a couple of days of this there would be a timid probing attack: if there were resistance the pounding would resume.”* “A second striking aspect of Israeli military doctrine exemplified in the Lebanese campaign,” he notes, “is the military exploitation of a cease-fire.

Israel has done this so often, in every one of its wars, that perhaps one must assume that for the Israeli military ‘cease-fire’ only means ‘no shooting’ and is totally unconnected with any freezing of positions on the ground along a ‘cease-fire’ line.” We have, in fact, noted several earlier examples of exploitation of cease-fire: the conquest of Eilat in 1949 and of the Golan Heights in 1967. “The Israelis, in this war, have refined their cease-fire-exploitation doctrine by declaring cease-fires unilaterally, at times most advantageous to them. This has left them free to switch cease-fires on and off with a show either of peaceful intent or of outraged indignation. For the Israelis the cease-fire is not a step towards a truce or an armistice, it is simply a period of rest, reinforcement and peaceful penetration-an attempt to gain the spoils of war without fighting.” Such tactics are possible because of the huge military advantage that Israel enjoyed.

* Israeli troops in fact often warned inhabitants to leave before the land sea and air pounding, but many report, not surprisingly that they were unaware of the warnings see Michael Jansen, The Bathe of Beirut Furthermore the leaflets sometimes were dropped well after the bombardment of civilian targets began as in Sidon. It has repeatedly been claimed that Israel suffered casualties because ofthe policy of warning inhabitants to leave but it remains unexplained how this came about in areas that were sure to be next on the list, warning or not and how casualties could be caused by the use of the tactics just described, which are repeatedly verified in the Israeli press Danny Wolf, formerly a commander in the Paratroopers, asks “If someone dropped leaflets over Herzliya [in Israel] tomorrow, telling the civilians in iliding to evacuate the town within two hours, wouldn’t that be a war crime?‘ (Amir Oren, Koteret Rashit, Jan.19, 1983). It would be interesting to hear the answer from those who cite these alleged IDF warnings with much respect as proof of the noble commitment to “purity of arms.”

Since the western press was regularly accused in the United States of failing to recognize the amazing and historically unique Israeli efforts to spare civilians and of exaggerating the scale of the destruction and terror-we return to some specifics-it is useful to bear in mind that the actual tactics used were entirely familiar and that some of the most terrible accounts were given by Israeli soldiers and journalists.

In Knesset debate, Menachem Begin responded to accusations about civilian casualties by recalling the words of Chief of Staff Mordechai Our of the Labor Party after the 1978 invasion of Lebanon under the Begin government, cited on p.181. When asked “what happens when we meet a civilian population,” Our’s answer was that “It is a civilian population known to have provided active aid to the terrorists… Why has that population of southern Lebanon suddenly become such a great and just one?”

Asked further whether he was saying that the population of southern Lebanon “should be punished,” he responded: ‘And how! I am using Sabra language [colloquial Hebrew]: And how!” The “terrorists” had been “nourished by the population around them.” Our went on to explain the orders he had given: “bring in tanks as quickly as possible and hit them from far off before the boys reached a face-to-face battle.” He continued: “For 30 years, from the war of independence to this day, we have been fighting against a population that lives in villages and in towns…” With audacity bordering on obscenity, Begin was able to utter the words: “We did not even once deliberately harm the civilian population. all the fighting has been aimed against military targets…”

Turning to the press, Tom Segev of Ha’aretz toured “Lebanon after the conquest” in mid-June. He saw “refugees wandering amidst swarms of flies, dressed in rags, their faces expressing terror and their eyes, bewilderment…, the women wailing and the children sobbing” (he noticed Henry Kamm of the New York Times nearby; one may usefully compare his account of the same scenes). Tyre was a “destroyed city”; in the market place there was not a store undamaged. Here and there people were walking, “as in a nightmare.” “A terrible smell filled the air”-ofdecomposing bodies, he learned.

Archbishop Georges Haddad told him that many had been killed, though he did not know the numbers, since many were still buried beneath the ruins and he was occupied with caring for the many orphans wandering in the streets, some so young that they did not even know their names. In Sidon, the destruction was still worse: “the center of the town-destroyed.” “This is what the cities of Germany looked like at the end of the Second World War.” “Half the inhabitants remained without shelter, 100,000 people.” He saw “mounds of ruins,” tens of thousands of people at the shore where they remained for days, women driven away by soldiers when they attempted to flee to the beaches, children wandering “among the tanks and the ruins and the shots and the hysteria,” blindfolded young men, hands tied with plastic bonds, “terror and confusion.”

✍

Danny Rubinstein of Davar toured the conquered areas at the war’s end. Virtually no Palestinians were to be found in Christian-controlled areas, the refugee camps having been destroyed long ago. The Red Cross give the figure of 15,000 as a “realistic” estimate ‘of the number of prisoners taken by the Israeli army. In the “ruins of Am el-Hilweh,” a toothless old man was the youngest man left in the camp among thousands of women, children and old men, “a horrible scene.”

Perhaps 350-400,000 Palestinians had been “dispersed in all directions” (“mainly women, children and old men, since all the men have been detained”). The remnants are at the mercy of Phalangist patrols and Haddad forces, who burn houses and “beat the people.” There is no one to care for the tens of thousands of refugee children, “and of course all the civilian networks operated by the PLO have been annihilated, and tens of thousands of families, or parts of families, are dispersed like animals.” “The shocking scene of the destroyed camps proves that the destrudtion was systematic.” Even shelters in which people hid from the Israeli bombardments were destroyed, “and they are still digging out bodies”-this in areas where the fighting had ended over 2 months earlier. An Oxfam appeal in March 1983 states that “No one will ever know how many dead are buried beneath the twisted steel of apartment buildings or the broken stone of the cities and villages of Lebanon.”

By late June, the Lebanese police gave estimates of about 10,000 killed. These early figures appear to have been roughly accurate. A later accounting reported by the independent Lebanese daily An-nahar gave a figure of 17,825 known to have been killed and over 30,000 wounded, including 5500 killed in Beirut and over 1200 civilians killed in the Sidon area. A government investigation estimated that 90% of the casualties were civilians. By late December, the Lebanese police estimated the numbers killed through August at 19,085, with 6775 killed in Beirut, 84% of them civilians.

Israel reported 340 IDF soldiers killed in early September, 446 by late November (if these numbers are accurate, then the number of Israeli soldiers kifled in the ten weeks following the departure of the PLO from Lebanon is exactly the same as the number of Israetis killed in all terrorist actions across the northern border from 1967). According to Chief of Staff Fitan, the number of Israeli soldiers killed “in the entire western sector of Lebanon” – that is, apart from the Syrian front – was 117. Eight Israeli soldiers died “in Beirut proper,” he claimed, three in accidents. If correct (which is unlikely), Eitan’s figures mean that five Israeli soldiers were killed in the process of massacring some 6000 civilians in Beirut, a glorious victory indeed. Israel also offered various figures for casualties within Lebanon. Its final accounting was that 930 people were killed in Beirut including 340 civilians, and that 40 buildings were destroyed in the Beirut, 350 in all of Lebanon. The number of PLO killed was given as 4000.

/Shatila © Ivana Peric, MER/

/Shatila © Ivana Peric, MER/

The estimates given by Israel were generally ridiculed by reporters and relief workers, though solemnly repeated by supporters here. Within Israel itself, the Lebanese figures were regularly cited; for example, by Yizhar Smilanski, one of Israel’s best-known novelists, in a bitter denunciation of Begin (the “man of blood” who was willing to sacrifice “some 50,000 human beings” for his political ends) and of the society that is able to tolerate him.

In general, Israeli credibility suffered seriously during the war, as it had in the course of the 1973 war. Military correspondent Hirsh Goodman reported that “the army spokesman [was] less credible than ever before.” Because of repeated government lies (e.g., the claim, finally admitted to be false, that the IDF returns fire only to the point from which it originates), “thousands of Israeli troops who bear eye-witness to events no longer believe the army spokesman” and “have taken to listening to Radio Lebanon in English and Arabic to get what they believe is a credible picture of the war.”

The “overwhelming majority of men-including senior officers”-accused lsraeli military correspondents of “allowing this war to grow out of all proportion to the original goals, by mindlessly repeating official explanations we all knew were false.” The officers and men “of four top fighting units. . accused [military correspondents] of covering up the truth, of lying to the public, of not reporting on the real mood at the front and of being lackeys of the defence minister.”

Soldiers “repeated the latest jokes doing the rounds, like the one about the idiot in the ordnance corps who must have put all Israeli cannon in back to front. ‘Each time we open fire the army spokesman announces we’re being fired at…”’ Goodman is concerned not only over the deterioriation in morale caused by this flagrant lying but also by Israel’s “current world image.” About that, he need not have feared too much. At least in the U.S., Israeli government claims continued to be taken quite seriously, even the figures offered with regard to casualties and war damages.

As relief officials and others regularly commented, accurate numbers cannot be obtained, since many-particularly Palestinians-are simply unaccounted for. Months after the fighting had ended in the Sidon area inhabitants of Am el-Hilweh were still digging out corpses and had no idea how many had been killed, and an education officer of the Israeli army (a Lieutenant Colonel) reported that the army feared epidemics in Sidon itself “because of the many bodies under the wreckage”.

Lebanese and foreign relief officials observed that “Many of the dead never reached hospital,” and that unknown numbers of bodies are believed lost in the rubble in Beirut; hospital figures, the primary basis for the Lebanese calculations cited above, “only hint at the scale of the tragedy.” “Many bodies could not be lodged in overflowing morgues and were not included in the statistics.”

The Lebanese government casualty figures are based on police records, which in turn are based on actual counts in hospitals, clinics and civil defense centers. These figures, according to police spokesmen, do “not include people buried in mass graves in areas where Lebanese authorities were not informed.” The figures, including the figure of 19,000 dead and over 30,000 wounded, must surely be underestimates, assuming that those celebrating their liberation (the story that Israel and its supporters here would like us to believe) were not purposely magnifying the scale of the horrors caused by their liberators. Particularly with regard to the Palestinians, one can only guess what the scale of casualties may have been.

A UN report estimated 13,500 severely damaged houses in West Beirut alone, thousands elsewhere, not counting the Palestinian camps (which are-or were-in fact towns). As for the Palestinians, the head of the UN Agency that has been responsible for them, Olof Rydbeck of Sweden, said that its work of 32 years “has been wiped out”; Israeli bombardment had left “practically all the schools, clinics and installations of the agency in ruins.”

✍

Beirut: Precision Bombardment

Repeatedly, Israel blocked international relief efforts and prevented food and medical supplies from reaching victims.* Israeli military forces also appear to have gone out of their way to destroy medical facilities-at least, if one wants to believe Israeli government claims about “pinpoint accuracy” in bombardment. “International agencies agree that the civilian death toll would have been considerably higher had it not been for the medical facilities that the Palestine Liberation Organization provides for Its own people”’and, in fact, for many poor Lebanese-so it is not surprising that these were a particular target of attack.

In the first bombing in June, a children’s hospital in the Sabra refugee camp was hit, Lebanese television reported, and a cameraman said he saw “many children” lying dead inside the Bourj al Barajneh camp in Beirut, while “fires were burning out of control at dozens of apartment buildings” and the Gaza Hospital near the camps was reported hit.” This, it will be recalled, was in “retaliation” for the attempt by an anti-PLO group with no base in Lebanon to assassinate Ambassador Argov.

On June 12, four bombs fell on a hospital in Aley, severely damaging it. “There is nothing unusual” in the story told by an operating room assistant who had lost two hands in the attack; “That the target of the air strike was a hospital, whether by design or accident, is not unique either,” William Branigan reports, noting that other hospitals were even more badly damaged. Fragments of cluster bombs were found on the grounds of an Armenian sanitarium south of Beirut that was also “heavily damaged during the Israeli drive.”

A neurosurgeon at the Gaza hospital in Beirut “insists that Israeli gunners deliberately shelled his hospital,” it was reported at the same. A few days later, Richard Ben Cramer reported that the Acre Hospital in Beirut was hit by Israeli shells, and that the hospitals in the camps had again been hit. “Israeli guns never seem to stop here,” he reported from the Sabra camp, later to be the scene of a major massacre:

“After two weeks of this random thunder, Sabra is only a place to run through.”

Most of this was before the bombing escalated to new levels of violence in August. By August 4, 8 of the 9 Homes for Orphans in Beirut had been destroyed, attacked by cluster and phosphorus bombs. The last was hit by phosphorus and other rockets, though clearly marked by a red cross on the root after assurances by the International Red Cross that it would be spared.

On August 4, the American University hospital was hit by shrapnel and mortar fire. A doctor “standing in bloodstained rags” said: “We have no more room.” The director reported: “It’s a carnage. There is nothing military anywhere near this hospital.” The hospital was the only one in Beirut to escape direct shelling, and even there, sanitary conditions had deteriorated to the point where half the intensive-care patients were lost and with 99% of the cases being trauma victims, there was no room for ordinary illnesses. “Drive down any street and you will almost always see a man or woman with a missing limb.”

One of the true heroes of the war is Dr. Amal Shamma, an American-trained Lebanese-American pediatrician who remained at work in Beirut’s Berbir hospital through the worst horrors. In November, she spent several weeks touring the U.S., receiving little notice, as expected. She was, however, interviewed in the Village Voice, where she described the extensive medical and social services for Palestinians and poor Lebanese that were destroyed by the Israeli invasion.

For them, nothing is left apart from private hospitals that they cannot afford, some taken over by the Israeli army. No medical teams came from the U.S., although several came to help from Europe; the U.S. was preoccupied with supplying weapons to destroy. She reports that the hospitals were clearly marked with red crosses and that there were no guns nearby, though outside her hospital there was one disabled tank, which was never hit in the shellings that reduced the hospital to a first-aid station. On one day, 17 hospitals were shelled.

Hers “was shelled repeatedly from August 1 to 12 until everything in it was destroyed.” It had been heavily damaged by mid-July, as already noted. Hospital employees stopped at Israeli barricades were told: “We shelled your hospital good enough, didn’t we? You treat terrorists there.” Recall that this is the testimony of a doctor at a Lebanese hospital, one of those liberated by the Israeli forces, according to official doctrine.

One of the most devastating critiques of Israeli military practices was provided inadvertently by an Israeli pilot who took part in the bombing,

An Air Force major, who described the careful selection of targets and the precision bombing that made error almost impossible. Observing the effects, one can draw one’s own conclusions. He also expressed his own personal philosophy, saying “if you want to achieve peace, you should fight.” “Look at the American-Japanese war,” he added. “In order to achieve an end, they bombed Hiroshima and Nagasaki.”

✍

The Grand Finale

Israel’s attack continued with mounting fury through July and August, the prime target now being the besieged city of West Beirut. By late June, residential areas had been savagely attacked in the defenseless city. Robert Fisk writes that “The Israeli pilots presumably meant to drop their bombs on the scruffy militia office on Corniche Mazraa, but they missed. Instead, their handiwork spread fire and rubble half the length of Abu Chaker Street, and the people of this miserable little thoroughfare-those who survived, that is-cannot grasp what happened to them… Abu Chaker Street was in ruins, its collapsed apartment blocks still smoking and some of the dead still in their pancaked homes, sandwiched beneath hundreds of tons of concrete… The perspiring ambulance crews had so far counted 32 dead, most of them men and women who were hiding in their homes in a nine-storey block of flats, when an Israeli bomb exploded on its roof and tore down half the building.”

One old man “described briefly, almost without emotion, how [his daughter’s] stomach had been torn out by shrapnel.” “This was a civilian area,” he said. “The planes are terrorizing us. This is no way for soldiers to fight.”’ This was before the massive air attacks of late July and August.

On one occasion, on August 4, the IDF attempted a ground attack, but withdrew after 19 Israeli soldiers were killed. The IDF then returned to safer tactics, keeping to bombing and shelling from land and sea, against which there was no defense, in accordance with familiar military doctrine. The population of the beleaguered city was deprived of food, water, medicines, electricity, fuel, as Israel tightened the noose.

Since the city was defenseless, the IDF was able to display its light-hearted abandon, as on July 26, when bombing began precisely at 2:42 and 3:38 PM, “a touch of humor with a slight hint,” the Labor press reported cheerily, noting that the timing, referring to UN Resolutons 242 and 338, “was not accidental.”

The bombings continued, reaching their peak of ferocity well after agreement had been reached on the evacuation of the PLO. Military correspondent Hirsh Goodman wrote that “the irrational, unprovoked and unauthorized bombing of Beirut after an agreement in principle regarding the PLO’s withdrawal had been concluded between all the parties concerned should have caused [Defense Minister Sharon’s] dismissal,” but did not.

The Il-hour bombing on August 12 evoked worldwide condemnation, even from the U.S.. and the direct attack was halted. The consensus of eye witnesses was expressed by Charles Powers:

To many people. in fact, the siege of Beirut seemed gratuitous brutality. . . The arsenal of weapons, unleashed in a way that has not been seen since the Vietnam war, clearly horrified those who saw the results firsthand and through film and news reports at a distance. The use of cluster bombs and white phosphorus shells, a vicious weapon. was widespread.

The Israeli government, which regarded news coverage from Lebanon as unfair, began to treat the war as a public-relations problem. Radio Israel spoke continually of the need to present the war in the “correct” light. particularly in the United States. In the end, however, Israel created in West Beirut a whole set of facts that no amount of packaging could disguise. In the last hours of the last air attack on Beirut, Israeli planes carpet-bombed Borj el Brajne [a Palestinian refugee camp]. There were no fighting men left there. only the damaged homes of Palestinian families, who once again would have to leave and find another place to live. All of West Beirut, finally, was living in wreckage and garbage and loss.

But the PLO was leaving. Somewhere, the taste of victory must be sweet.

✍

Read more on Chomsky.info.

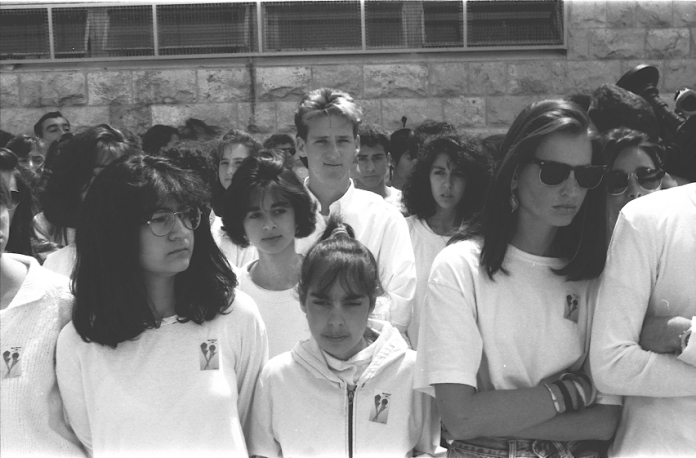

/Photo: Izkor/

/Photo: Izkor/ /photo: Izkor/

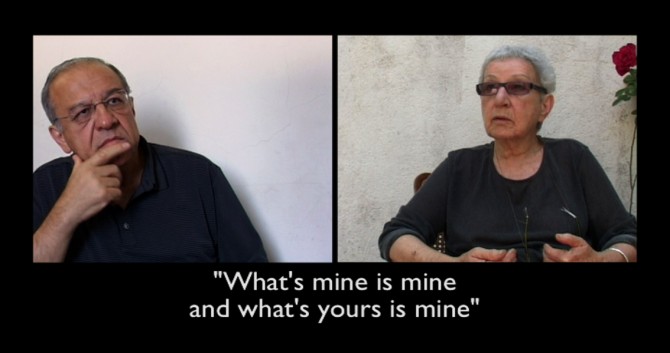

/photo: Izkor/ /Photo: Common State/

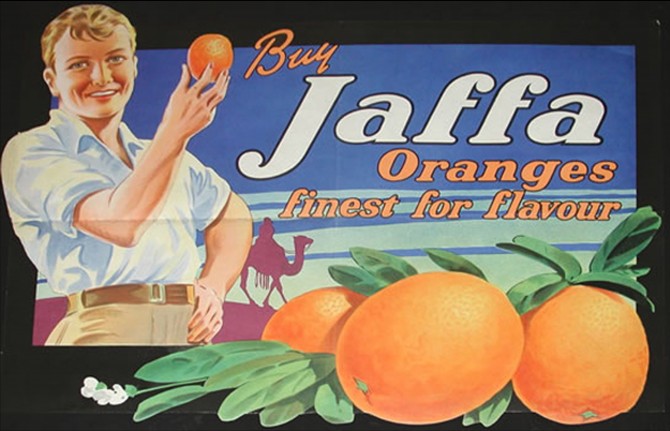

/Photo: Common State/ /Photo: Jaffa – The Orange’s Clockwork/

/Photo: Jaffa – The Orange’s Clockwork/