This week, Istanbul on my mind. So much change in the last couple of years. In Istanbul, in Turkey, in countries around Turkey. A terrifying game of dominos, it seems.

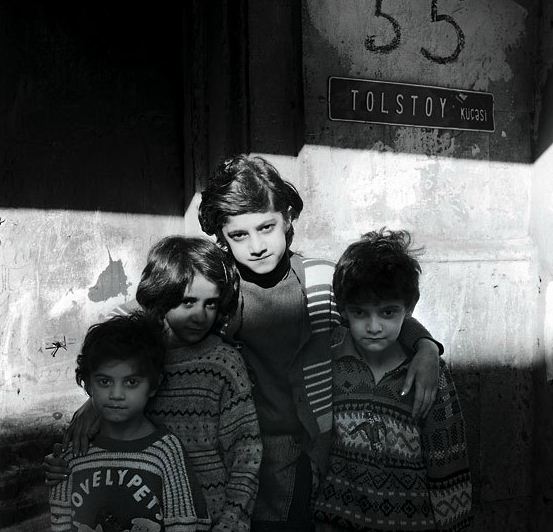

I thought about Rena Effendi’s work The Last Dance of Tarlabasi, done in 2011. It makes me nostalgic because that is when and where I first time fell in love with Istanbul. With Effendi’s great work, Tarlabasi and its magic remain captured in time.

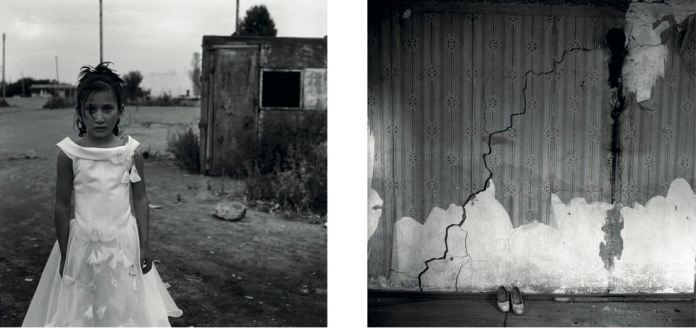

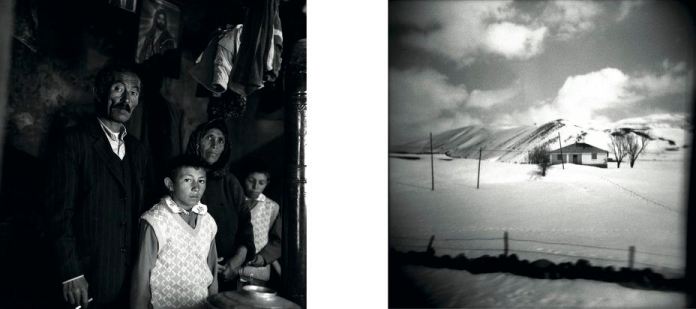

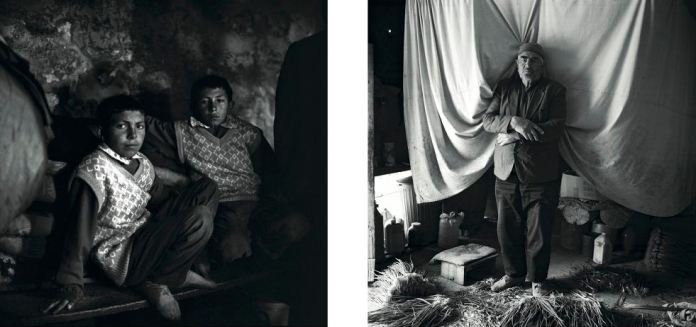

In spite of its run-down looks and reputation for widespread crime, Tarlabasi was a culturally vibrant neighborhood kaleidoscope – populated by Kurdish migrant workers from Anatolia, Roma gypsies, Greeks and African immigrants – from devout Muslims to trans-gender sex workers.

But a big change happened – in 2011, Beyoglu municipality began a series of forced evictions – following the government’s plan for city “beautification”. Effendi described how as a result of this urban development initiative, many of the current Tarlabasi residents were being “bought out” and ordered to leave, as their homes are demolished to accommodate the construction of upscale residences.

Entire building blocks in Tarlabasi have been sold off to private companies, transforming the streets into ghostly barracks, pending reconstruction. Many of the neighborhood’s residents, their faces and lifestyles did not fit in with the new, “modern”, mandated look of Tarlabasi.

Last Dance of Tarlabasi is a visual tale of this neighborhood and the way it struggled to survive the ruthless pace of Istanbul’s urban change.

All of this is captured very well in a sentence told by Ali Ber, a 45-year-old Kurdish migrant from Mardin. “I’ve lived here for more than 20 years; all my children grew up here. Why should I leave? If they want to make Tarlabasi better, why can’t I be part of it?”, Ber asked.

How is the story of Tarlabasi revelant today, five years later? How is it relevant after the recent terrorist attacks in Instabul?

It is relevant because it shows what today’s world values, what capitalism values. Most of the people are getting eaten by the machine of capitalism, we are being crushed and squeezed, with very little place to breathe, to live decent lives.

We live in a time of crisis that cannot be fixed within the capitalist framework. Creating more and more fear is the method that is being used – since most of the world’s leaders and politicians don’t seem to care for (long-term) solutions.

People being pushed out of their homes, people dying in terrorist attacks, people being forced to work for way less than a minimum wage (it is slavery, so call it slavery), people jumping off bridges because they can’t pay the rent, people begging on streets, people selling kidneys to pay for their children’s education, people who dare to cross the sea in boats that look like walnut shells because there’s no safe ground for them, people who still don’t know where their children (their bodies) are because they happened to be at a wrong corner, at a wrong time, with wrong skin on their bodies and wrong language coming out of their mouth, people who live and die each day to see what wars (war on terror, war on drugs, war on war) look like on the ground, in reality – all of these people are the victims, and all of their stories are connected.

We are being forced to see these problems in a deeply fragmented way (which is exactly how the ruling classes of our time want us to see it), but we need to move beyond fragments and see how things are connected, how we are connected.

And when you think about things that way, it is easy to realize that we are all (well, 99 percent of us at least) dancing the last dance of Tarlabasi.

//all photos © Rena Effendi//

For more on Effendi and her work, go to her official website.