This year I still didn’t write anything about GTMO and it’s birthday (January 11th), so this is my version of congratulations card. The book Guantánamo Diary is written by Mohamedou Ould Slahi, still imprisoned Guantánamo detainee. It is the first ever public account written by a still-imprisoned Guantánamo detainee. Slahi has been in Guantánamo for twelve years, although United States has never charged him with a crime. A federal judge ordered his release in 2010, but he remains in custody.

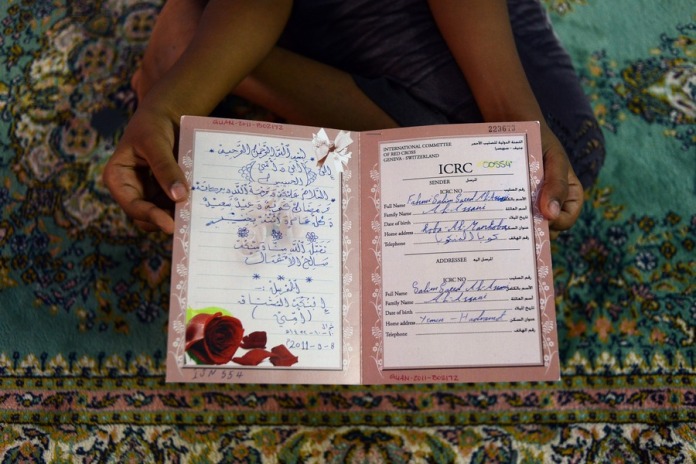

/Guantánamo Diary, photo via The FJP/

/Guantánamo Diary, photo via The FJP/

Three years into his captivity Slahi began a diary, recounting his life before he disappeared into U.S. custody, “his endless world tour” of imprisonment and interrogation, and his daily life as a Guantánamo prisoner. The following is an excerpt from Slahi’s diary.

Jordan–Afghanistan–GITMO

July 2002– February 2003

The American Team Takes Over … Arrival at Bagram … Bagram to GTMO … GTMO, the New Home … One Day in Paradise, the Next in Hell

July __, 2002, 10 p.m.

The music was off. The conversations of the guards faded away. The truck emptied. I felt alone in the hearse truck. The waiting didn’t last: I felt the presence of new people, a silent team. I don’t remember a single word during the whole rendition to follow.

A person was undoing the chains on my wrists. He undid the first hand, and another guy grabbed that hand and bent it while a third person was putting on the new, firmer and heavier shackles. Now my hands were shackled in front of me.

Somebody started to rip my clothes with something like a scissors. I was like, What the heck is going on? I started to worry about the trip I neither wanted nor initiated. Somebody else was deciding everything for me; I had all the worries in the world but making a decision. Many thoughts went quickly through my head. The optimistic thoughts suggested, ‘Maybe you’re in the hands of Americans, but don’t worry, they just want to take you home, and to make sure that everything goes in secrecy.’ The pessimistic ones went, ‘You screwed up! The Americans managed to pin some shit on you, and they’re taking you to U.S. prisons for the rest of your life.’

I was stripped naked. It was humiliating, but the blindfold helped me miss the nasty look of my naked body. During the whole procedure, the only prayer I could remember was the crisis prayer, Ya hayyu! Ya kayyum! and I was mumbling it all the time. Whenever I came to be in a similar situation, I would forget all my prayers except the crisis prayer, which I learned from life of our Prophet, Peace be upon him.

One of the team wrapped a diaper around my private parts. Only then was I dead sure that the plane was heading to the U.S. Now I started to convince myself that “every thing’s gonna be alright.” My only worry was about my family seeing me on TV in such a degrading situation. I was so skinny. I’ve been always, but never that skinny: my street clothes had become so loose that I looked like a small cat in a big bag.

When the U.S. team finished putting me in the clothes they tailored for me, a guy removed my blindfold for a moment. I couldn’t see much because he directed the flashlight into my eyes. He was wrapped from hair to toe in a black uniform. He opened his mouth and stuck his tongue out, gesturing for me to do the same, a kind of AHH test which I took without resistance. I saw part of his very pale, blond-haired arm, which cemented my theory of being in Uncle Sam’s hands.

The blindfold was pushed down. The whole time I was listening to loud plane engines; I very much believe that some planes were landing and others taking off. I felt my “special” plane approaching, or the truck approaching the plane, I don’t recall anymore. But I do recall that when the escort grabbed me from the truck, there was no space between the truck and the airplane stairs. I was so exhausted, sick, and tired that I couldn’t walk, which compelled the escort to pull me up the steps like a dead body.

Inside the plane it was very cold. I was laid on a sofa and the guards shackled me, mostly likely to the floor. I felt a blanket put over me; though very thin, it comforted me.

I relaxed and gave myself to my dreams. I was thinking about different members of my family I would never see again. How sad would they be! I was crying silently and without tears; for some reason, I gave all my tears at the beginning of the expedition, which was like the boundary between death and life. I wished I were better to people. I wished I were better to my family. I regretted every mistake I made in my life, toward God, toward my family, toward anybody!

I was thinking about life in an American prison. I was thinking about documentaries I had seen about their prisons, and the harshness with which they treat their prisoners. I wished I were blind or had some kind of handicap, so they would put me in isolation and give me some kind of humane treatment and protection. I was thinking, What will the first hearing with the judge be like? Do I have a chance to get due process in a country so full of hatred against Muslims? Am I really already convicted, even before I get the chance to defend myself ?

I drowned in these painful dreams in the warmth of the blanket. Every once in a while the pain of the urine urge pinched me. The diaper didn’t work with me: I could not convince my brain to give the signal to my bladder. The harder I tried, the firmer my brain became. The guard beside me kept pouring water bottle caps in my mouth, which worsened my situation. There was no refusing it, either you swallow or you choke. Lying on one side was killing me beyond belief, but every attempt to change my position ended in failure, for a strong hand pushed me back to the same position.

I could tell that the plane was a big jet, which led me to believe that flight was direct to the U.S. But after about five hours, the plane started to lose altitude and smoothly hit the runway. I realized the U.S. is a little bit farther than that. Where are we? In Ramstein, Germany? Yes! Ramstein it is: in Ramstein there’s a U.S. military airport for transiting planes from the Middle East; we’re going to stop here for fuel. But as soon as the plane landed, the guards started to change my metal chains for plastic ones that cut my ankles painfully on the short walk to a helicopter. One of the guards, while pulling me out of the plane, tapped me on the shoulder as if to say, “you’re gonna be alright.” As in agony as I was, that gesture gave me hope that there were still some human beings among the people who were dealing with me.

When the sun hit me, the question popped up again: Where am I? Yes, Germany it is: it was July and the sun rises early. But why Germany? I had done no crimes in Germany! What shit did they pull on me? And yet the German legal system was by far a better choice for me; I know the procedures and speak the language. Moreover, the German system is somewhat transparent, and there are no two and three hundred years sentences. I had little to worry about: a German judge will face me and show me whatever the government has brought against me, and then I’m going to be sent to a temporary jail until my case is decided. I won’t be subject to torture, and I won’t have to see the evil faces of interrogators.

After about ten minutes the helicopter landed and I was taken into a truck, with a guard on either side. The chauffeur and his neighbor were talking in a language I had never heard before. I thought, What the heck are they speaking, maybe Filipino? I thought of the Philippines because I’m aware of the huge U.S. military presence there. Oh, yes, Philippines it is: they conspired with the U.S. and pulled some shit on me. What would the questions of their judge be? By now, though, I just wanted to arrive and take a pee, and after that they can do whatever they please. Please let me arrive! I thought; After that you may kill me!

The guards pulled me out of the truck after a five-minute drive, and it felt as if they put me in a hall. They forced me to kneel and bend my head down: I should remain in that position until they grabbed me. They yelled, “Do not move.” Before worrying about anything else, I took my most remarkable urine since I was born. It was such a relief; I felt I was released and sent back home. All of a sudden my worries faded away, and I smiled inside. Nobody noticed what I did.

✎

Read the book Guantánamo Diary, for it is a rare window into the turture, pain, anxiety, and enormous injustice that shapes the lives of the detainees. Like Slahi, most of them spent numerous years of their lives in prison, with no charges against them. With that reality pressing him, Slahi still remains an optimist, a remarkable spirit caught in dreadful circumstances. Still, he survives, he lives, he writes. It’s upon us to atleast read what he has to say. The book is dedicated to his mother Maryem Mint El Wadia, who died while he was imprisoned.